The Queering of Right-Wing Populism

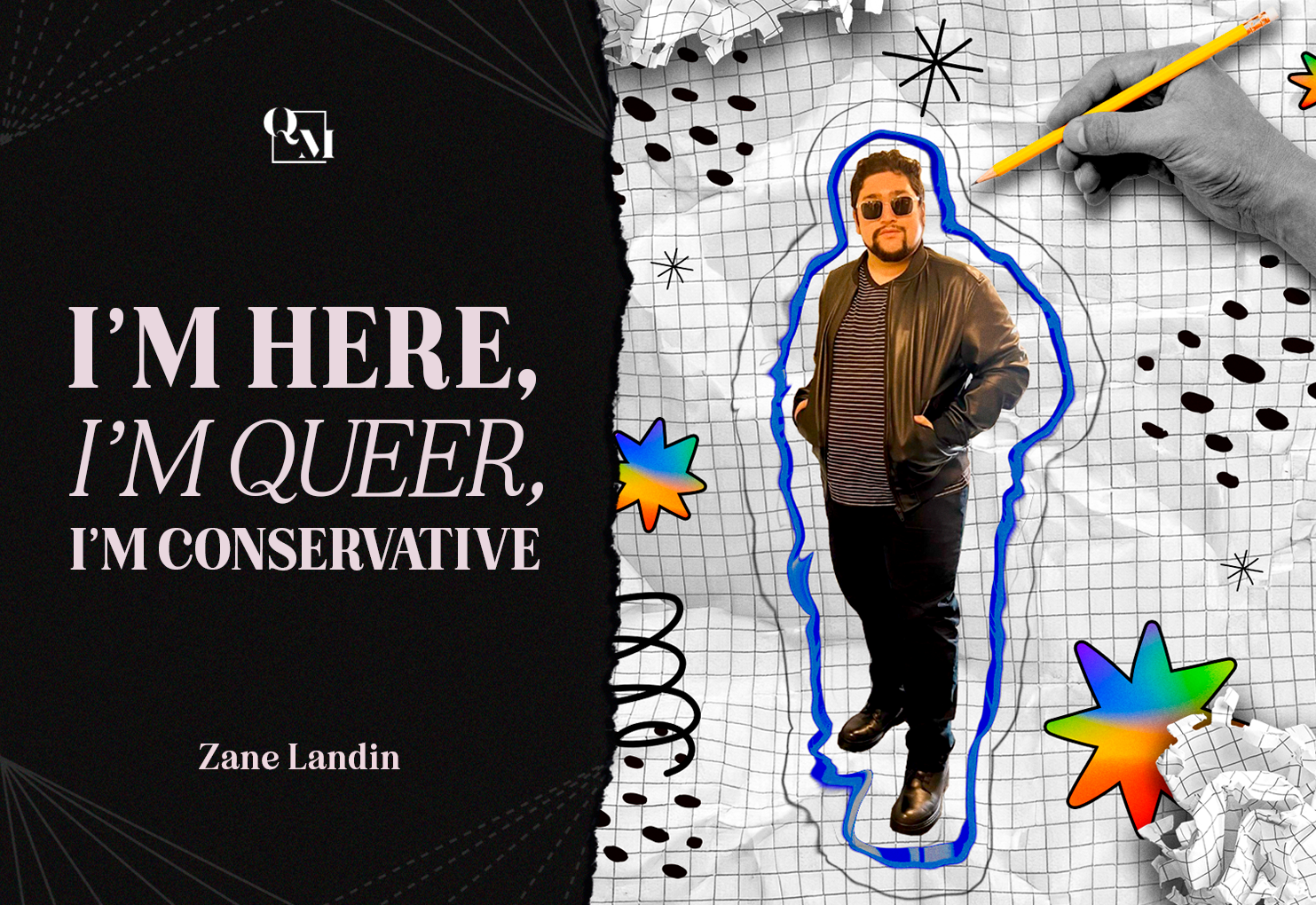

For decades, the mainstream narrative insisted that LGBT people were synonymous with progressivism. Queerness, we were told, was inherently radical, inherently left-wing, and inherently bound to the politics of transgression and resistance. That story was never quite true. LGBT people have never been a political monoculture, even if they’ve been painted as such. But lately, even that perception is falling apart.

Across the Western world, a growing number of LGBT people are aligning with right-wing, nationalist, and libertarian movements. This isn’t just political heresy — it’s a cultural earthquake. And while the progressive establishment scrambles to denounce this ideological defection, many are quietly stepping out of the orthodoxy. In the United States, for example, just 39% of LGBT voters in 2025 are registered Democrats — down from 56% in 2013 — and nearly half identify as politically moderate or conservative.

This shift may unsettle traditional LGBT advocacy organizations, but it signals something far more profound: a rejection of ideological gatekeeping in favour of intellectual autonomy, political pluralism, and a commitment to values that transcend identity.

LGBT individuals have always defied easy categorization. The idea that being gay, lesbian, bisexual, or trans must align one with the political left is a relatively modern construct, born of the 1960s sexual revolution and shaped by decades of culture-war rhetoric. Even in the early days of the LGBT rights movement, there were ideological splits.

In the US, groups like the Mattachine Society and the Homophile Movement of the mid-20th century were politically moderate and integrationist LGBT organizations that laid much of the groundwork for later activists. The Log Cabin Republicans emerged in the 1970s, challenging the assumption that sexual orientation dictated political allegiance. These gay and bi conservatives didn’t deny their sexuality — they simply refused to reduce it to a political ideology. They championed capitalism, small government, and personal freedom. For that, they were treated as traitors by the very movement they helped build. But that marginalization may have inadvertently paved the way for a new kind of LGBT political consciousness — one grounded not in victimhood but in volition.

In Canada, this ideological divergence is quietly taking root. Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre, long dismissed as a populist firebrand, has found surprising support among LGBT Canadians — particularly those disillusioned by progressive performativity and the condescending moralism of elite urban progressives. It’s worth noting that in Canada, 71% of people on the political right support same-sex marriage. Poilievre doesn’t court LGBT voters with rainbow flags or empty gestures. He does so by talking about housing affordability, free speech, and the erosion of civil liberties. His appeal isn’t about identity — it’s about agency. In doing so, he has tapped into a constituency of LGBT Canadians who are tired of being reduced to a checkbox on a political platform.

These individuals are often working-class, economically pragmatic, and deeply skeptical of the moral codes imposed by progressive gatekeepers in recent years. They believe rights are best protected not by a state bureaucracy but by a culture of liberalism grounded in individual responsibility and free expression.

This political parting is perhaps most visible in the United States. GQ’s profile of the “‘Normal Gay Guys’ Who Voted for Trump” captured the cultural shock: white-collar, educated gay men who preferred economic growth and border control over symbolic virtue-signalling. The 25% of LGBT voters in 2020 and the 20% in 2024 who voted for Donald Trump weren’t seeking to have their rights taken away — they were voting for freedom, economic realism, and enforcing the border. They were people who’d grown tired of being told their sexuality or gender identity obligated them to support a hard left agenda. For them, Trump’s vulgarity wasn’t a bug — it was a feature. His refusal to bow to elite consensus was, paradoxically, liberating. These voters weren’t seeking inclusion in a progressive utopia. They were seeking freedom from leftist orthodoxy.

The past few years have also seen the rise of “anti-woke” and culturally right-wing LGB groups such as the UK-based LGB Alliance and the US-based “Gays Against Groomers.” These organizations, and others like them, take hostile stances against trans activism and oppose what they see as the left-wing ideological indoctrination of children in the name of queer advocacy. In turn, they’re often labeled as extremists, bigots, and useful idiots for the far right. But the rise of these groups reflects a growing cultural fracture within the LGBT community — particularly around gender ideology, which they see as having hijacked the entire LGBT movement and replaced a fight for legal equality with a crusade for ideological conformity.

These critics argue that children are being medicalized, propagandized, and used as political pawns by a movement that has abandoned liberal values in favour of radical social engineering. Whether one agrees with them or not, their rising influence reveals a realignment underway — one in which the fight for gay, lesbian, and bi rights is increasingly decoupled from the left-wing activist class. And it’s not just LGB people. Trans political activists such as Brianna Wu have increasingly voiced concerns about the damage done to the trans community by these same activist overreaches.

Perhaps the most natural ideological home for many disaffected LGBT people is libertarianism. Libertarianism values autonomy over solidarity, freedom over social control, and individualism over collectivism. For many LGBT individuals, this philosophy offers something the political left no longer can: the right to dissent.

Public figures like Konstantin Kisin have given voice to this new queer individualism. Though straight himself, Kisin’s critiques of identity politics and moral authoritarianism resonate with many LGBT people who feel increasingly alienated from the cultural left. LGBT libertarians aren’t interested in rainbow-washed government programs or ideological purity tests. They want to be left alone — to love who they want, speak how they want, and live without intrusive micromanagement. In this light, queerness becomes not a tool of resistance but a manifestation of personal freedom. This is exemplified by the fact that the US Libertarian Party began supporting same-sex marriage decades before the Democrats.

One of the most controversial — and least discussed — reasons why many LGBT people have gravitated toward right-wing populist movements is the cultural clash between liberal democracy and multiculturalism. The left, in its uncritical commitment to multiculturalism, refuses to acknowledge that not all cultures are equally tolerant or liberal. It is a bitter irony: the same activists who protest drag queen bans in Texas will condemn as racist any critique of violent homophobia in immigrant communities. In the US, a country with a long track record of successfully integrating waves of immigrants, this disconnect is less pronounced. But for many LGBT people living in Europe, this hypocrisy is a matter of survival.

In Sweden, gay men have reported harassment and threats in areas with high populations of migrants from countries where homosexuality is illegal. In Germany, concerns over unregulated immigration have even caused some LGBT people to join the far-right populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), not out of bigotry, but because they see it as the only party willing to defend borders. These voters are not naïve about the far-right’s history. But they are also not willing to ignore the present danger posed by reckless policies and misguided ideologies that threaten to roll back hard-won rights. For them, right-wing populism — however flawed — is a survival strategy.

The unavoidable truth is that LGBT individuals are not a monolith. And the assumption that same-sex attraction or trans identity must be synonymous with left-wing politics is not only reductive — it’s intellectually dishonest. What we are witnessing is not a betrayal of the LGBT legacy, but a maturation of it. An assertion that queerness is not a political orientation but a human reality that can — and should — exist across ideological lines.

Rather than regarding the political dispersal of LGBT people as cause for worry, we can just as easily see it as an affirmation that gay, lesbian, bi, and trans folks contain within them the same multitudes and diversity of thought that every other area of society does. If the progressive movement cannot make peace with that fact, it will continue to lose LGBT voters to parties that, while imperfect, at least acknowledge their right to think freely. LGBT people are, first and foremost, not a class, or a tribe, or a “community”, but individuals. Maybe the path forward is simply to treat them as such.

Published July 03, 2025