My Body and Other Adventures: Finding Race

I was a remarkably oblivious child. In some ways, this made me more than a little socially awkward, but it also insulated me from many of society’s expectations and judgments. I lived in my head so much of the time that I failed to realize when I was being treated differently than others. I was sublimely unselfconscious, and it was lovely.

Ethnically, I am half-Korean. While I joke that this is the reason I love pickles so so much, in truth, I have no connection to my Korean-ness. My ethnically Korean mother was adopted in infancy by a white couple and raised in Reno, Nevada. She was one of seven children, some of whom were the couple’s natural offspring, and some of whom were, like her, adopted from other cultures. It was a complicated family dynamic. Eventually, she joined the United States Army and was stationed in Korea, which is where she met my father, who was also stationed there. As children, both my parents grew up on grilled cheese sandwiches and ambrosia salads. Thankfully, the latter was no longer in their repertoire by the time I came around.

If you look at pictures of me with all my paternal cousins, you’ll see one ethnically ambiguous kid with long black pigtails in a sea of blonde. I have over 40 cousins on my dad's side of the family, and I am the only one whose hair and complexion doesn’t fall somewhere between white blonde and dirty blonde. At the time, though, thanks to my obliviousness, I never gave this any thought. It was not until many years later when looking at family photos that I realized how much I stood out.

When I was five years old, my dad was stationed in an idyllic little town in Bavaria, Germany. I went to a local German school, and although I stuck out like a sore thumb, so many things made me weird besides my race that I never thought of it. I didn’t speak the language at first, I didn’t dress like the other kids, and I didn’t eat the same foods as them. I was dealing with so many immediate cultural differences that I remained mostly oblivious to everything else. Looking back, this was an intense period in my life, despite how young I was. I was so worried about the time I accidentally called myself a toilet that I didn’t have the energy to notice any racial politics happening around me. They were happening, no doubt, but I was shielded from them by being overwhelmed and unaware. Hindsight reveals a fuller picture.

Along with many of my classmates, I went to summer camp. It was advertised to my atheist parents as vaguely protestant. At this point, I was interpreting for them and I am sure much was lost in translation, but it was free and that fit their budget, so off I went. It was a strange blend of hippie and generic Protestantism. Our counselors were 16 or 17, and even then, it was clear they were eager to get us all stowed away for the night so that the real party could start. We swam in the lake, sang old American gospel songs (I’m still not sure why), and were generally filthy mud-caked hellions. It was wonderful. Since it was the 1990s, this meant that I came home with a bright hair wrap every year.

This is how I found myself, at around eight years old, quietly perusing the children’s section of the military base’s bookstore. My mom was nowhere to be seen, off looking for her own books. A man randomly came up to me and complimented my hair wrap. I thanked him awkwardly and went back to my books. Instead of leaving, though, he continued by asking me about my tribe. Now I was confused. He explained that he thought I was Native American and wanted to know more about my people.

At that moment, I became what is now commonly referred to as “a person of color”. This was the first time I remember being aware that people saw me differently because of my skin tone. Not only that, but they made assumptions about me because of what they saw. They assumed that they knew something about me, my faith, my cultural heritage, or my citizenship. They saw my skin color and thought they knew me much more deeply than they possibly could.

This incident was largely innocuous — nothing bad came of it. I didn’t feel offended or ashamed. Mostly, I was just confused. After that, I started to observe my differences more, though. I noticed how surprised people seemed when I spoke flawless German or English, how often they asked me where I was really from, and many of the other little instances that folks would now call “microaggressions”.

Since then, there have been other equally strange experiences. I have had people scold me for denying my heritage by pretending I can’t speak Spanish (I can’t). There have been horrified looks when my Korean friends learned that I didn’t own a rice cooker (I do now and they were right). There have also been moments of camaraderie when I made eye contact with the only other person of color in the room, and knew that they were rolling their eyes at the same thing as me.

As an oblivious child, I needed a lens through which to interpret these occurrences. I needed a historical and cultural context to explain why someone might assume that I wouldn’t speak unaccented English, that I would belong to a tribe, or that I would own a rice cooker. My obliviousness could not protect me forever.

Identifying as a person of color gave me that lens. I learned about the history of black and brown people in the United States, and about our shared and unique experiences. It gave me a way to talk about structural problems, microaggressions, and good old-fashioned racism. Connecting with the past gave me a way to talk about my own racial identity. This sense of history and belonging was especially important to me because I was not raised with any sense of my Korean-ness.

The fact that I don’t feel any real connection to the culture that gave me my skin color and that I appear ethnically ambiguous has made me more aware of my racial identity. We often think of identity as something fundamentally empowering, that by choosing one we demarcate ourselves. We should all be able to define ourselves on our own terms. However, all the recent energy and celebration around identity disguises the unpleasant truth: that many of us choose our identities in reaction to society’s expectations.

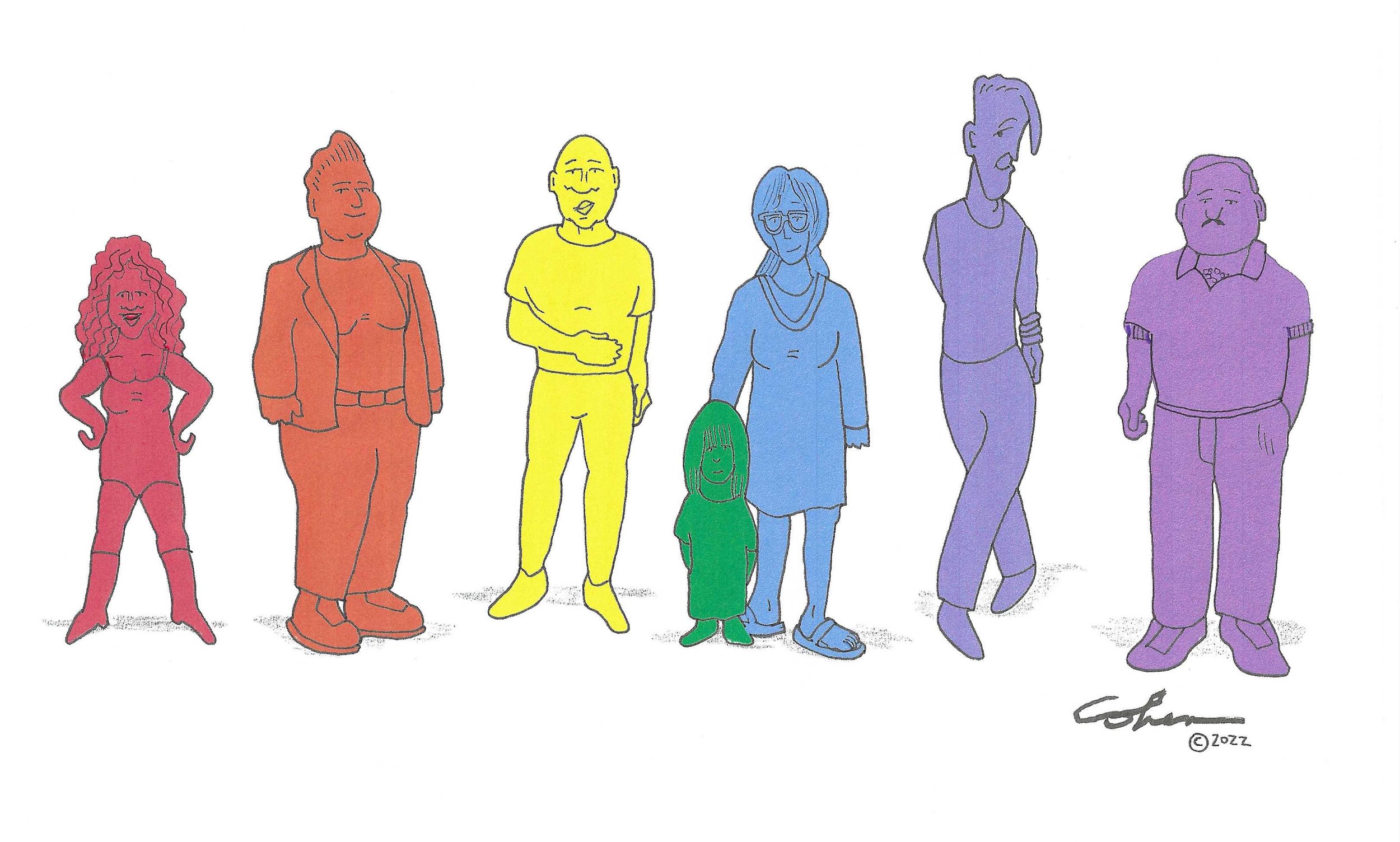

No matter how we see ourselves, we will still have to deal with other people’s assumptions, and these assumptions will often inform how we create our sense of self. I am undeniably not white. This is a fact of my skin color. For me, the political reality of race and of being a person of color wasn’t really a choice. Yes, I choose to identify that way, and there are probably situations under which I could “pass”, but I am not even going down that rabbit hole. For all intents and purposes, my choice was either to embrace my POC identity as a way to push back against everyday racism, or to attempt to spend the rest of my life hiding from others. So, I chose the former. The important thing to remember is that even when society forces its expectations upon us, our identities give us a way to unite, to push back, and to define ourselves on our own terms.

Published May 1, 2020

Updated Dec 19, 2022

Published in Issue VI: Identity