Confessions of a Sexual Politics Infiltrator

Back in 1988, I was a card-carrying communist and, together with a group of fellow revolutionaries, I attempted to infiltrate a lesbian and gay rights group to exploit it for my own ends.

Although it took place 35 years ago, my story raises questions that are still pertinent in 2023: especially given the growing split within the LGBTQ+ union — between the LGBT on one side and the Critical Social Justice-inspired TTQQIAAPK2S+ on the other. The countermovement #LGBWithoutTheT has been growing, and some of its members claim that the lesbian and gay rights movement has been infiltrated by critical trans and queer activists, who are more interested in promoting their revolutionary politics than defending the dignity of love and sex between consenting adults.

In 1988, British gay culture had almost nothing to do with politics of any kind — let alone sexual politics. The far-left viewed gay culture as hedonistic, libidinal, decadent, depoliticised, and deeply capitalist — more about nightclubs than protest marches. Nonetheless, we communists saw the emerging gay and lesbian rights struggle as tactically convenient.

I was 20 at that time, and a member of the Socialist Workers Party — a Trotskyist revolutionary organisation that had a smattering of adherents across the world. We were deeply committed to mobilising the masses and instigating a Marxist revolution, based on the Leninism/Trotskyism of the 1920s. In the 80s, the SWP was part of what the tabloids called the loony left — a quaint British expression for a plethora of competing anti-democratic, ultra-left parties.

However, I wasn’t entirely comfortable with being a member of the SWP — or with being an exclusively straight man. I was a timid, closeted, tentative bisexual — at a time before the B was included in the LGBT abbreviation. A decade later, I would become one of the lo-fi, indie New Queer Cinema directors, but in the late 80s I was caught in the gap between sex and politics. The idea that the personal is (and should be) political had not yet become a popular mantra. Mouths and genitals had not yet become entwined with flags.

And then, in 1988, the government passed Clause 28, and young communist me was thrust into the reality of sexual politics.

Clause 28

Clause 28 (or Section 28) of the Local Government Act 1988 introduced a series of laws that instructed local authorities across the UK not to “intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.” The bill, passed by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, came into effect in England, Scotland, and Wales in May 1988. Its main purpose was to get what the government saw as gay propaganda out of classrooms. Under the new legislation, teachers were not to “promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.”

Clause 28 was partly a reaction to London’s socialist city councils, who were using state funds to introduce more lesbian and gay content into schools and to subsidise lesbian and gay groups and centres. According to one report (cited in the Sunday Telegraph, 6 October 1985), Islington and Haringey local councils and the Greater London Council together donated around £600,000 to gay and lesbian projects and groups in 1984 (£1,788,000 or $2,180,463 in today’s money).

The conservatives hoped that Clause 28 would help depoliticise sex but, ironically, it had exactly the opposite effect. (Please note that by sex, I don’t mean sexual identity.)

By November, there were massive political demonstrations against Clause 28. Tens of thousands took to the streets to protest the homophobia, bigotry, and censorship that the new legislation implied. Most of their protest signs referred to lesbian and gay rights (they didn’t include bi or trans people).

This festival of protest provided us revolutionary communists with a great opportunity. We didn’t care about gay and lesbian rights: we were a puritanical bunch who regarded any focus on sexuality as reactionary. But, just as we tried to use the 1984–85 miners’ strike to kick-start a general strike, which we hoped would provoke mass rioting and lead to a revolution, we saw the gay and lesbian protestors as a tool that we could use to smash capitalism. We didn’t believe in gay rights any more than we believed in democracy or truth-telling. All those things were simply to be used strategically to achieve our goal of revolution.

Our Infiltration Strategies

After decades of unsuccessfully trying to convert people to the cause, we had learned that it is more strategically effective to infiltrate single-issue groups and take them over from within — just as the revolutionary communist group known as Militant infiltrated Liverpool City Council in 1983–87 and brought the city to a standstill. According to UK security service MI5, the Communist Party also infiltrated schools and attempted to take over the National Union of Teachers. The Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) was also infiltrated by communist activists, who were inspired by the anarchic free schools of the 1970s and taught children to be anti-capitalist warriors — while neglecting basic literacy. (The Times Educational Supplement reported on this in its January 1986 print-only edition, in an article entitled “The Ultra-Left Tightens Grip on Schools.”)

In the 80s, we commies were obsessed with infiltration. We didn’t want to fix any individual problems. We weren’t reformists. Instead, we wanted to make society’s problems even worse, until a liberatory revolution would seem like the only possible solution. We dreamed of bringing all the single-issue groups together to make one vast bonfire.

People protesting against Clause 28 in Manchester, February 1988.

How effective were we at infiltrating the resistance to clause 28?

If you look carefully at the picture above, you can spot actor Ian McKellen and now veteran campaigner Peter Tatchell. You’ll also notice the protest signs emblazoned with the logo of the Socialist Workers Party. We handed hundreds of these out to grateful lesbian and gay protestors. About a third of the protest signs at these demos were carried by non-Communists, who unwittingly promoted our brand for us, helping get our name into newspaper and TV reports.

They had no idea they were being played. But how effective was the infiltration? The best way to answer this is by telling my own story.

The Night Three Fellow Trotskyists and I Attempted to infiltrate a Glasgow STOP CLAUSE 28 Meeting

(Disclaimer: This story features some real-life people. Names have been changed.)

The Scene

A city-council-owned community hall in a state of disrepair. The place usually hosted AA meetings, judo, keep-fit classes, bingo for the over-sixties, basket weaving — and the occasional group of five people who were planning to take over the world. It smelled of cigarettes, mould, sweat, and Pine air freshener. That night, the room was going to be rented out to six gay men and two lesbians who were planning to fight Clause 28 — plus myself and three other members of the Glasgow branch of the Socialist Workers Party (which only had 18 members in total).

The Cast

Aiden (mid-20s): our leader was an arts student who considered himself a Marxist intellectual. He was an ex-Catholic — a great talker, though he was prone to get tied up in the minutiae of academic jargon.

Old Jim (early 50s): a die-hard working-class veteran of the local SWP, a chain-smoking unemployed former union man. Old Jim rarely said anything but “aye” or “no”, generally followed by a Trotskyite slogan. He was one of the paleo left: an old-timer entirely focused on the proletariat, the unions, and class war. The SWP was his last hope for society.

Tommy (mid-30s): impatient and volatile. He attacked a police horse during the 1985 miners’ strike. Every week, he stalwartly attempted to sell copies of Socialist Worker on street corners and could be heard muttering “bourgeois bastards” at the shoppers who walked past, trying to ignore him. I was always a little scared of Tommy because he considered me effete and middle-class, and I sensed that he was brimming with latent homophobia. In retrospect, he was perhaps not the best person to take to a Clause 28 meeting.

And me (20): a socially awkward, sexually confused, hippie-ish, middle-class, art student, desperate for a political panacea that would solve all the world’s problems.

Before infiltrating the lesbian and gay group, the four of us decided to hold an impromptu strategy meeting in a doorway a few blocks away from the community hall.

Aiden: So, we go in, we listen to them, we offer our support, we try to avoid saying anything that’ll scare them off and then we try to lead them towards a more general opposition to the Tory government.

Old Jim: Aye, connect the single issues.

We wanted the single-issue groups to merge — to get the anti-Clause 28 bunch to stand with the nurses and the students, even though the demonstrations against student loans and the nurses’ pay strikes had nothing to do with Clause 28. This was Trotskyism 101: bringing all the disaffected together in solidarity was the only way to instigate the general strike that would trigger a violent revolution. Anything short of this we considered reactionary and middle class.

Aiden: Remember, we don’t call ourselves comrades in front of them. We don’t admit we’re part of the same group. We walk in separately.

Old Jim: Aye.

Tommy: I bet they’re all middle class, eh? I know a few poofs and they’re more interested in shopping than class politics.

Aiden: We don’t say that word either, comrades. Remember, we’re on their side. Be calm, be generous and watch what you say. Gaining their trust is going to take longer than just one meeting.

In my seven months as a Socialist Worker, I had not encountered a single other new recruit. I was beginning to have grave doubts about the SWP’s ability to take over the world.

So, one by one, we communists entered the meeting — though the pretence that we didn’t know each other collapsed as soon as Old Jim and Tommy sat down next to each other.

The lesbian and gay group contained three memorable characters.

The Cast, continued

Sal (mid-30s): a schoolteacher. She was a second-generation radical feminist. She had a crew cut and was dressed in the style of the lesbian in-crowd of the time called diesel dykes.

Damon (late-20s): an attractive middle-class gay man, brimming with enthusiasm, proud to be out. He had worked in television and was a bit of a yuppie.

Tim (mid-20s): in the lingo of the time, he was a scene or clone gay, working class, dressed in fashionable sportswear, all glitzy rings and hair gel. He was immediately suspicious when we, four unknown men, entered the room.

Sal took charge of the meeting. She had experience running school union meetings and things went pretty smoothly at first. She gave us an update on the latest news and the relevant legal challenges and passed round a list for us to fill in our names and contact details and a petition to sign. But I could sense Tim’s eyes on me, and I was beginning to feel more and more like an impostor. Maybe it had been a mistake for Tommy and Old Jim to sit next to each other — especially since neither of them looked at all gay. Or maybe Tommy had already started muttering something under his breath about middle-class traitors and poofs.

For a while, though, everything was fine. Sal said she was disappointed by the turnout but happy to welcome the newcomers. Damon stood up and talked about how difficult it was to get news coverage but reported that they were having some success with the London press. Then our SWP leader, Aiden, stood up and made an impassioned speech about how Clause 28 was an appalling violation of the rights of minorities.

“Aye”, muttered Old Jim — and maybe, through force of habit, he added the word “comrade.” And as Aiden went on and on — as if he were Trotsky himself, giving one of his finest speeches since 1921 — I could sense Tim eyeing the four of us and smiling. Finally, he shook his head, stood up, and said, “Sorry, who are you?” in a tone that clearly implied that the real question was “What are you doing here?”

In all his infiltration planning, Aidan had overlooked the fact that Glasgow’s out gay scene was pretty tight at that time, comprising only a couple of pubs and a single nightclub. So, strangers really stood out. Plus, when cornered, Aidan tended to retreat into ever more grandiose declarations of universal solidarity.

“I mean,” Tim said, “are you gay, mate?”

Sal objected, “I think we want to stay open to anyone who’s interested in fighting this thing. We need all the supporters we can get.”

“No but really”, Tim said, “If you’re not gay …”

“Or lesbian”, interjected Sal.

“Yeah”, Tim continued, “so if you’re not, then Clause 28 doesn’t affect you in any way. So, what are you doing here?”

A general muttering ensued and then someone quietly remarked, pointing at Old Jim, “I’ve seen that guy before, selling newspapers.” Then someone else said, “Aye, what’re they called, the RCP [Revolutionary Communist Party] or something?”

At which point our Tommy exploded. To be accused of being an RCP member was a major insult. You see, at this time, in true Monty Python style, all the far-left groups — the Socialist Workers Party, Militant, the Workers Revolutionary Party, the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Socialist Party, and the Revolutionary Communist Party — despised each other even more than they despised our capitalist overlords. As in The Life of Brian (1979), the RCP was the Judean People’s Front to our People’s Front of Judea.

Our game of covert infiltration was up. I felt mortified at having been caught, but also sickened at the thought that we’d invaded a private meeting between people who had a real problem, in the real world, which they wanted to fix.

“Wait, how many people here are in the RCP?” asked Damon, the handsome television man. He was right to raise this, as the RCP had a history of sabotaging Labour Party by-elections, including one in 1983, in which their heckling destroyed the electoral chances of gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell.

Sal tried to hold the collapsing meeting together, but by the time Tommy had angrily retorted, “We’re the SWP, not those cunts, the RCP!” it was over for us.

Things quickly descended into chaos. Aidan, Tommy, and Old Jim stormed out — Tommy uttering classic homophobic curses under his breath — while I just stood there, frozen, too ashamed to leave with my so-called comrades.

As the room was clearing, Damon came over to me, and said, “We’re heading to the pub. Fancy coming?” “Uhm, sorry”, I stammered, “but I’m one of them” (meaning: a member of the SWP).

Damon laughed. “Well, I’m one of them too!”

He was inverting an old anti-gay slur. I laughed.

On the way to the local gay pub, I tried to apologise for the way in which we had trashed their meeting, but he was nonchalant about it. “Oh, we come across loonie lefties all the time”, he said. “Not that I’m saying you’re a loony.”

I had never been to a real gay bar before, although I’d had a few discreet encounters with men. I sat down with Damon and several others from the meeting, including Tim, in a cosy back corner. They asked, laughing, what a nice guy like me was doing with a bunch of numpties like the SWP. I was flattered and grateful to have been admitted to their circle. And so I told them how the SWP did this with other groups too — with the students and the nurses, for example.

Tim — who scared me a bit — leaned in and said, “The thing is, I don’t want some commies poking their noses into my sex life. Or Maggie Thatcher for that matter. It’s nobody’s business. Don’t want any politicians telling me who I can or cannot fuck.”

“Yes”, Damon added, “I mean, some of the women we know, like Sal, they’re all about the personal is political, but I agree with Tim: there’s far too much politicisation of sex. It’s a bit like the Nazis, sorting everyone out into types when they should just leave us alone to do what we want.”

“Yeah”, said Tim, “fuck politics.”

As the evening progressed and we got in a few more rounds, I confided in Damon that I might be bisexual.

He smiled and said, “Ah, I thought you might be. I mean not bi, but gay.”

Tim leaned in again. “There’s no such thing as bi. Either you’re gay or you’re not. It’s in your DNA. If you’re bi, it just means you’re in the closet or you’re a fantasist, with a head full of images and doing nothing.”

“Bisexual is just an idea in your head”, someone else said, “like dressing up as something. Either you fuck or you don’t.”

Tim added, “Yeah, you are what you eat!” and everyone burst out laughing. Double entendre dick-themed gags and casual biphobia were de rigueur at the time.

Damon squeezed my hand. “Sorry about all that”, he said and gave me his number.

Two weeks later, I left the Socialist Workers’ Party (but I stayed bi).

A year later, the Berlin Wall fell, the USSR collapsed, and all the communist parties in the West — big and small — disbanded or went into decline. The SWP has withered away to almost nothing now, although they still hand out free signs at protests.

We would-be communists didn’t manage to infiltrate the lesbian and gay rights movement. But others were to succeed where we had failed.

The Next Generation of Radical Infiltrators

By the year 2000, Clause 28 had been overturned in Scotland (the rest of the UK followed suit in 2003). It was a political own-goal for the conservatives. The protests against Clause 28 unified and strengthened the lesbian and gay rights movement in the UK. Stonewall was founded in 1989, as a direct response to Clause 28 (once again, Peter Tatchell was a central figure). Nothing creates unity like a common enemy. Over the decades, the LG movement expanded to include first the B, then the T and Q until, in some versions, it’s now the unwieldy LGBTTQQIAAPK2S+.

Meanwhile, the old left had to morph into various new forms in order to survive. The psychoanalytic new left got stuck in an academic cul-de-sac, but the postmodern queer left took off. It appropriated sexuality, but it moved away from concerns about biological sex to focus on the concept of gender. In postmodern academia, pride in your identity was the new solution to LGBT issues. It was no longer primarily about biology and sexual behaviour/attractions, but about self-identification. Actual sex acts were no longer even necessarily involved.

As ideas about the self took precedence over facts about relationships, a new oppressed class was born. They were no longer defined by interactions between bodies, but fixated on redefining abstract concepts and dismantling every traditional structure in society.

By the 2000s, the new revolutionaries were scoffing at gay men, whom they saw as depoliticised, sex-crazed, capitalist sell-outs — just as the SWP had done.

We’ve since witnessed the return of the kind of political games we communists were attempting to play that night in Glasgow: the political hijacking of a movement that was about safeguarding people’s rights to physical relationships with each other in the here and now, in favour of an abstract future revolution. The Queer+ movement, in its more radical strains, is all about revolutionary ideology.

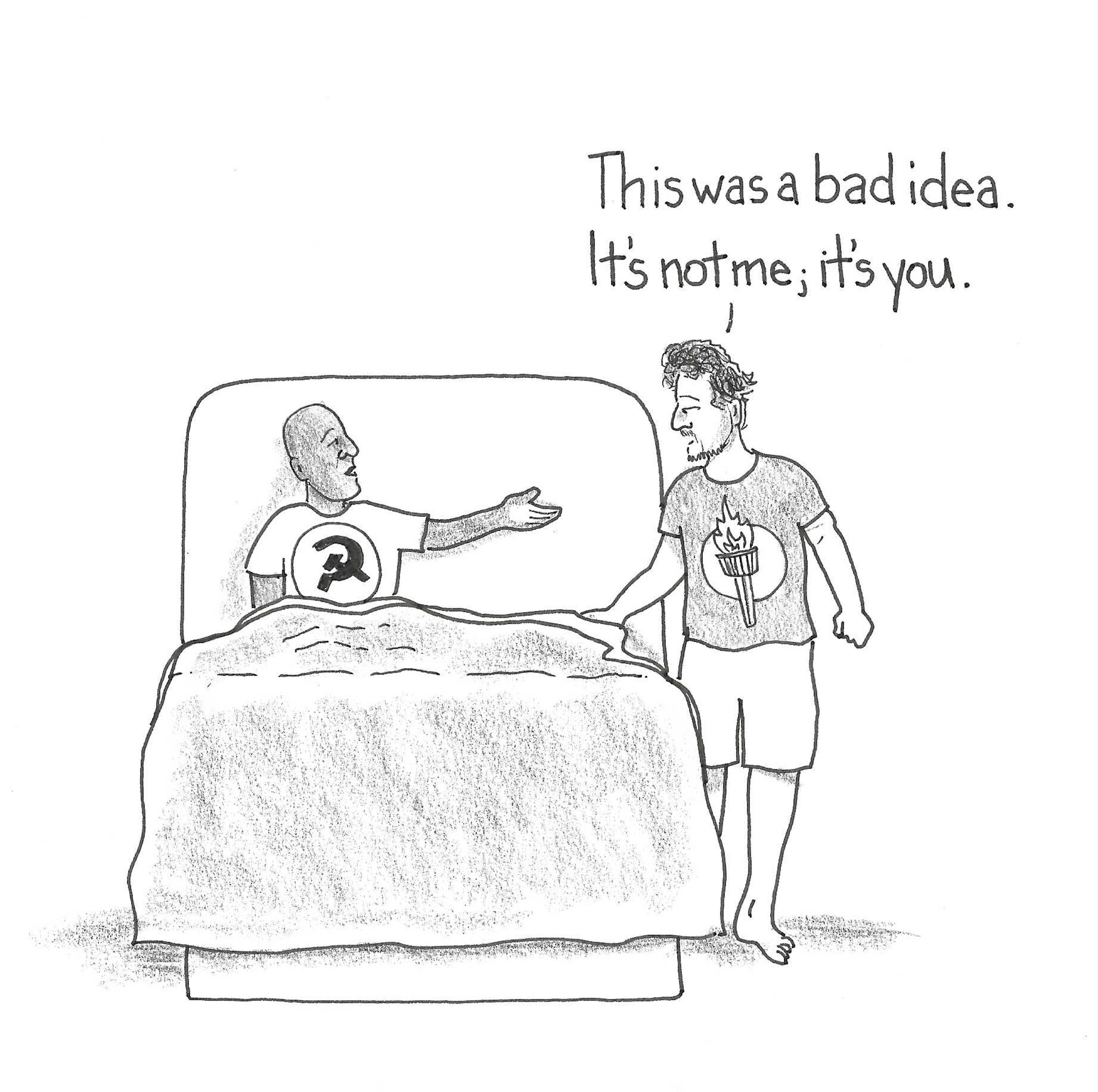

This division is a split between people who want to keep politics out of their private lives and people who want to force their identity politics into everyone else’s. It’s a split between people who are concerned about the bodies they currently inhabit and the relationships they currently have versus people — like my old communist buddies — who are fighting for some undefined ideal that doesn’t yet exist and for an abstract notion of the possibility of relationships in some future utopian state that will probably never exist. They want to remake mankind.

The communists wanted to remake humanity, too. Technology, they believed, would facilitate the creation of the new Soviet man and eradicate the difference between the sexes. And they were ready to sacrifice everything and everyone in pursuit of that dream.

Some people claim that the queer-communist connection is just cosplay. If you’ve seen vintage Soviet propaganda posters get an “incredible LGBT makeover”, you might concur.

And yet many queer people do talk ecstatically about a future in which technology has allowed us to create the post-capitalist utopia of fully automated luxury gay space communism. On Reddit forums, you can find lots of people discussing this coming revolution, in which “gender and other such harmful constructs are abolished, making everybody queer/gay.” The hammer and sickle often appear alongside the pride flag, and, since the 1990s, many university professors have made the transition from an increasingly ossified Marxism to the new evolving queer theory, bringing a large contingent of students with them. One scholar even wrote a Ph.D. paper arguing that my own book, Tales from the Mall (2012), and Ali Smith’s novel Hotel World (2001) were part of the queer revolutionary canon.

Today, critical queerness is hailed by many as the new revolutionary force that will liberate us from oppressive social constructs like patriarchal, cisgendered normativity. If Antonio Gramsci rose from his grave, he would undoubtedly cast down his worm-eaten red flag and reach for a bright new 13-coloured rainbow one. He did, after all, kick-start the long march through the institutions with his conviction that the family and all associated traditional roles had to be destroyed. He was “queer” before his time.

Yet, the new postmodern identity activism isn’t as directly tied to Marxist lineage as some have claimed. It’s not collectivist enough, given how many confused liberals are in this motley coalition — it’s far too focused on individualistic things like identity and it has only achieved power because it has gained the support of techno-capitalism. No political movement that has the support of most major corporations can really be considered communist or far-left. The new rainbow revolution has been brought to you by ASDA, Apple, Astra Zeneca, Bank of America, Converse, Este Lauder, GAP, IBM, IKEA, Johnson and Johnson, JP Morgan Chase, Microsoft, PayPal, Pfizer, Viacom, and Visa.

These postmodern identity radicals are not primarily concerned with material realities such as economics, property, or employment rights, as the old left was. They don’t go on strike. They don’t protest Big Business — they get sponsorship from major corporations. Instead, they attack words and images; they police people’s pronoun usage; they compel what they call inclusive speech. While intersectionalists shout anti-capitalism, they do a fine job of raking in corporate cash.

Postmodern identity radicalism is a strange hybrid of old communist ideas and modern-day advertising and PR. They are modern-day behaviourists — believing that they can affect societal change by forcing people to change the language they use.

But the fact that postmodern identity radicalism is a confusing political hybrid doesn’t mean it isn’t just as dangerous as old-school Marxism. The new radicals have been very successful at infiltration. Whenever you come across an inclusive language guide, they have won a victory for their linguistic social engineering project. Over the last few years, we’ve seen the infiltration of charities, quangos, and corporations. In some cases, this is simply companies trying to protect themselves from liability with overbearing diversity training, but ideological capture appears sincere in others. Oxfam recently issued an inclusive language guide that could have been lifted directly from Mao’s Cultural Revolution:

“Language has the power to reinforce or deconstruct systems of power that maintain poverty, inequality, and suffering. Choices in language can empower us to reframe issues, rewrite tired stories, challenge problematic ideas, and build a radically better future.”

Mao — one of the most brutal dictators of the 20th century — also believed in the destruction of all words and images that did not fit his vision of a planned society.

The Arts Council of England has been similarly infiltrated by those who want to mandate language control and there have also been attempts to remould language and imagery in Scotland through a gender recognition reform bill and a hate crime law. Most of us know of at least one organisation that has been infiltrated by those who want to force everyone to speak the language of their future utopia and outlaw wrongspeak — and even wrongthink. This is what Marxists call “driving the red wedge.”

This is not entirely a recent phenomenon. Many earlier activists — L, G, B, and T — have been tempted by the idea of socially engineering a world better-suited to the needs of their own identity group and infiltrating organisations to that end. The LGBT movement must take some blame for the rise of the critical Queer+ activists whom many of them are now so keen to be rid of.

How to Spot an Infiltrator

Radical postmodern identity infiltrators, like the SWP of old, don’t want to fix single issues, but to tie all issues together, since, for an activist, as Lenin put it, “the worse, the better.” They spread discontent and conflict in every situation from the workplace to the home, especially by attempting to mandate which words and images people can use.

They also despise everything about the current moment. The idea that you can solve your own problems and experience your own pleasures without their help is abhorrent to them. They aren’t fighting to safeguard or regain individual rights to privacy, freedom of choice, free speech, and dignity. They hate everything about the present because it does not match their radically egalitarian vision. They want vengeful payback; the oppressors must be destroyed. They see the gay men who want politics kept out of the bedroom as homo-normative slaves to bourgeois capitalism.

They are generally too ignorant of history to understand that the path they are on will lead to totalitarianism if they win — one with brightly coloured flags and sponsorship by Google and Bank of America.

If we cannot dissuade these radicals from imposing their goals on the rest of us, then our only option is to expose them and expel them from organisations and causes where they don’t belong — just as the SWP were turfed out of that meeting, back in 1988. The first step is to stand up and ask, “Who are you and what are you really doing here?”

Published May 30, 2023

Updated Jun 1, 2023