Children on the Pole

On a 2016 episode of the British broadcast show This Morning (1988 – ), two eleven-year-old girls and an eight-year-old stood around a pole. Wearing identical cropped dress shirts tied into a bow at their navels, each girl took her turn on the pole performing beginner’s moves: inverting upside down, hooking backward, and spinning around for a quick beat. Their mothers and dance teacher seated on a nearby couch explained how pole dancing had improved their daughters’ self-confidence. According to one mom, “Tilly was bullied at school for being fat and not interested in what the other girls did,” but following her enrollment in pole dancing classes, there was a noticeable improvement in her emotional well-being.

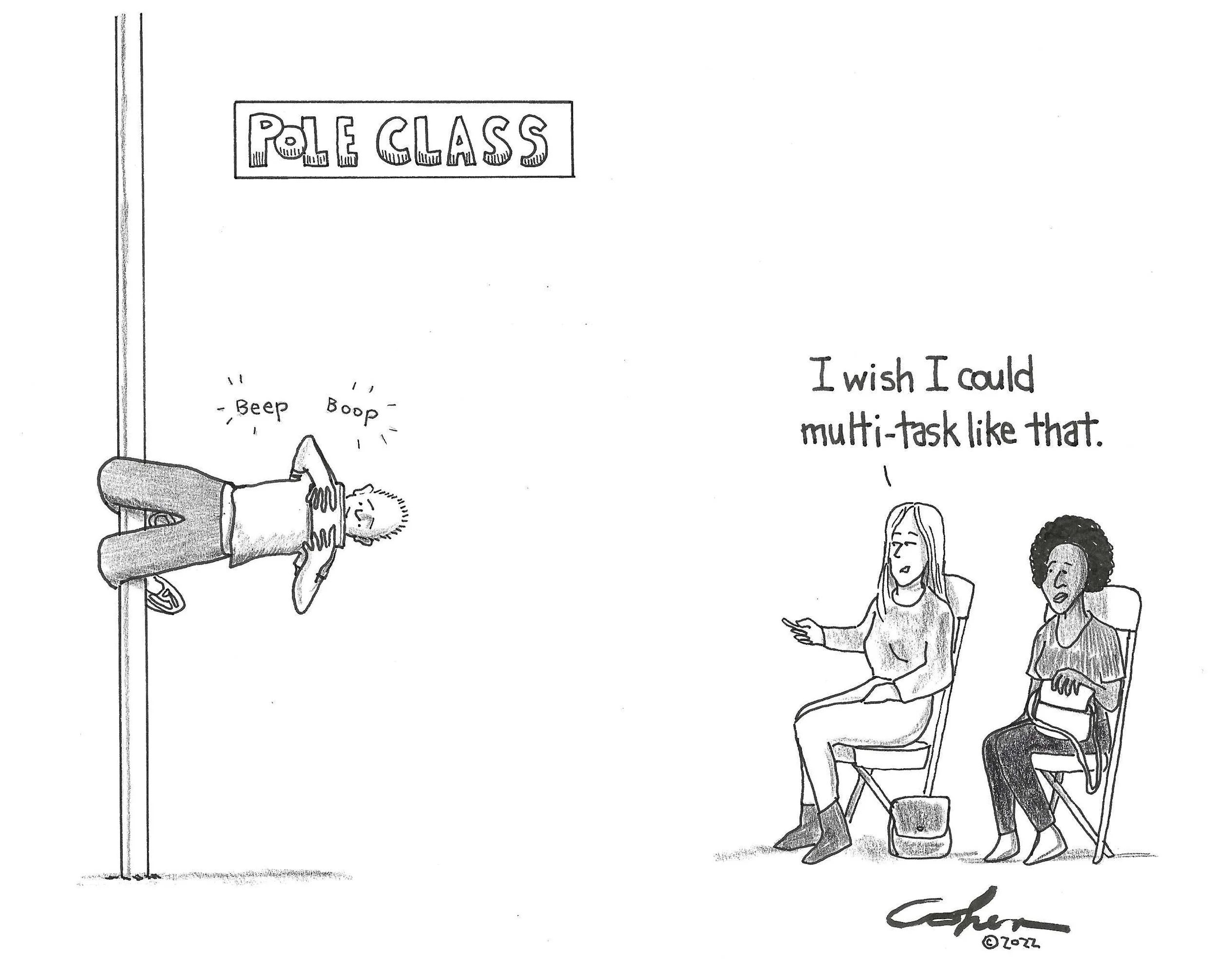

This comment is part of a growing push to get pole dancing recognized as a legitimate sport, which would open it up to children as an appropriate form of exercise. In 2017, these efforts garnered some success when pole was deemed a provisional sport by the Global Association of International Sports Federation. This classification means that while it is not yet considered prestigious enough for the Olympics, the skill and athleticism needed to master pole routines are starting to be recognized as being on par with gymnastics, diving, and ice skating.

Still, many people remain uncomfortable with the idea of children spinning around a pole, believing it to be too suggestive, provocative, and inappropriate to be considered kid-friendly. Is there any legitimacy to their concern?

To answer this question, one must first understand that pole dancing is more than just a fitness class or a sporting competition. It is also a job. And the job is one that is steeped in stigma. Although attitudes in some places like New Zealand might be changing, in most they are still overtly hostile towards sex workers. In the United States, for example, most strippers do not receive worker’s compensation if they are injured on the job, clubs are regularly raided and shuttered by police, and deaths are largely ignored.

The presumption that pole dancing is always exploitative is central to the stigma and negative attitudes surrounding it. Admiring a person’s body and performance isn’t exclusive to recognizing them as a human being. The notion that customers are categorically unable to see a stripper’s humanity is inaccurate and insulting. There is nothing inherently objectifying about dancing around a pole.

Sadly, rather than promoting sex positivity, much of this rise in popularity of pole dancing has been achieved by distancing it from the work done by dancers in the strip club. Consider the instructor’s insistence on This Morning that the tricks the girls executed were different from those invented and performed by strippers. “It’s pole fitness,” the instructor asserted when asked if it was appropriate for kids to perform pole tricks. “It’s different from the dancing you see in clubs.”

Efforts to bring pole dancing into the mainstream by separating it from stripping started in the early 2000s when studios began popping up in many English-speaking countries. These studios taught the pole tricks, floor work, and lap dance techniques that strippers developed in the club to students outside the sex industry. To encourage interest among these non-sex-working women, classes were marketed as something separate from sex work, framed as a way for all women to get fit and grow comfortable in their bodies and sexualities.

As classes grew in popularity, so too did this idea that pole was somehow distinct from the work of strippers. Many pole dancers sought to separate themselves from the stigma by posting videos of their latest tricks next to the hashtag “#notastripper”. Studios attempted to wipe away the stain of exotic dancing by arguing pole’s roots were in ancient Chinese and Indian forms of dance, even though it was strippers who created the first pole studios and taught the world the spins they mastered during long grueling shifts at the club.

The trouble with this narrative (aside from its inaccuracy), that pole fitness is cleaner and less provocative than stripping, is that it doesn’t reduce stigma against sex or sex work. Instead, it reinforces it. Consider one studio in South Africa that argues pole dancing is appropriate for children because “back in the eighties, [it] may have been synonymous with strippers and seedy men’s clubs, but today it’s about fitness, fun, confidence and community”. The implication is that strip clubs don’t promote any of these things, but if you ask any stripper, they will tell you this simply isn’t true. For a fitness industry to simultaneously copy and devalue erotic work is hypocritical and counterproductive to its goal of mainstream acceptance.

But what type of pole dancing is suitable? Since there is nothing inherently objectifying about dancing around a pole, there should be nothing inherently harmful about children participating in the sport. Still, I believe kids’ participation ought to occur in an age-appropriate manner.

While anyone can learn how to climb and whip around what is essentially a piece of the jungle gym, steps should be taken to ensure children’s participation does not negatively affect their sexual development. I think most of us can agree that the Peekaboo Pole (a kit marketed to children that includes a pole, sexy tunes, a garter belt, and fake dollar bills), is creepy and inappropriate. But ballet, which can also be highly sexual and is likewise a job that adults perform to entertain and excite crowds through dance, is seen as a perfectly reasonable sport for young people to participate in. Where and how did we draw the line?

In my view, the answer is this: it is okay for kids to want to feel beautiful. It is also okay for kids to learn tricks and explore how their bodies look and feel in space. We can and should work to adjust social attitudes by teaching older children about the original pole dancers and the stigma they face. But moves that overtly entice and arouse? Leave that for adults.

Like the mothers on This Morning discovered, pole dancing teaches spatial awareness, confidence, and body appreciation that can help a child’s development. We need to carve out a space for children to fly on poles that does not erase or further stigmatize the sex workers who originated the culture. Yes, it is important to draw a line between adult work and kid-friendly moves, but that doesn’t mean strippers can’t be acknowledged and admired for the jaw-dropping tricks they gave the world. There is plenty of room on the pole for everybody.

Published Jul 1, 2020

Updated Jan 4, 2023

Published in Issue VII: Sports